James Britton (1878-1936)

The man in the red hat is back. Work by the early 20th century artist James Britton returned to the Nabi Gallery in an exhibit opening September 23, 2004.

The Nabi 's first Britton show, at its former Sag Harbor space in 1999, also included 18 landscapes and seascapes painted in Sag Harbor in 1925—the first time these paintings had been seen on Long Island since that time. A later exhibit, reprised on these web pages, took a broader look at Brittons legacy, including scenes of both Sag Harbor and Connecticut, a group of portraits of himself and his family, and a selection of woodcut prints portraying cultural and historical figures he admired, among them Walt Whitman, Edgar Allan Poe, Abraham Lincoln, and Franz Joseph Haydn, as well as himself and his wife Carol.

.

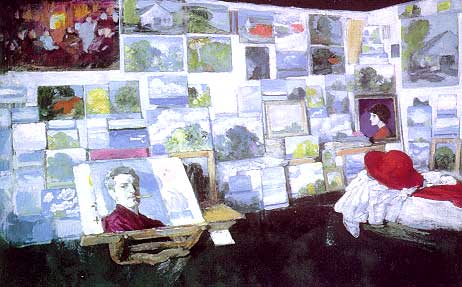

James Britton brought his family out from New York City in 1922 and took rooms on Main Street, upstairs from the office of the local newspaper, the Expressin the same building whose rear extension, fronting Route 114, housed the Nabi from 1996 to 2001. Among the larger pieces in the show was a scene of his Sag Harbor studio, its walls covered with his own paintings (several of them recognizably the same ones that would one day hang nearby in the gallery) and in one corner a bed with the red hat tossed on the pillow.

During his three years there, while Carol Britton supplemented the family income by playing piano accompaniment to silent movies at the Sag Harbor Cinema, he painted many views of bay and sky, quiet village lanes, and buildings such as the bootleggers storehouse visible from his studio window. He continued, however, to keep a studio in New York, where he reluctantly commuted by train, and where he produced the portraits and art criticism that were his main livelihood.

In his autobiography, begun in 1935, a year before his death in Hartford at the age of 58, he recalled his harbor of refuge here as a sleepy little village occupying a flat nub of land which could easily be cleaned off by a good-sized tidal wave. The harbor was nothing now, but old timers told me that it had been more than a little piece of sad blue waterit had been a whaling port. But now the only marine excitement was clam-digging.

In those days, he wrote, everybody went to Southampton, certain others went to East Hampton, and still others to Hampton Bays. No one went to Sag Harbor. That was as it should be. Very often I rolled in on the little steam train, in the dark, the sole passenger making the change from the New York train at Bridgehampton. I enjoyed the quiet, the solitude of this last lap of the journey from the city with its millions of rushing humans, its hideous noises, its whirls of never settled dust, its general continuous annoyances.

In Sag Harbor, he added, there were no artists except for a few amateurs. Going back and forth frequently, New York provided sufficient contact with the art profession. I wanted to get away from the strutting exhibitioners, and when some of them talked about following me down east, I gave them no encouragement.An illustrated selection from the autobiography and diaries, compiled by the artists granddaughters, Ursula and Barbara Britton, is available at the gallery.